Jasper Petrus Cornelis was die seun van Jasper Petrus Cornelis van der Westhuizen en Maria Elizabeth Zacharya Meintjies.

Sy naam kom voor in hulle pa se sterfkennis van 1901.

Sy naam kom voor in hulle ma se sterfkennis van 1917.

In the beginning, health was a major concern. Many of the people were desperately poor. The British authorities described them as ‘low class’, ‘hopeless, helpless, sick and vermin-ridden’. As in Pretoria, measles struck early and very severely and the MO remarked on the virulent character of the disease, complicated by pneumonia. Persistent diarrhoea and sore eyes suggest wider health problems. It was particularly difficult to keep the camps which were close to large towns free of disease, and infections appear to have been rife in Johannesburg. Measles was followed by scarlet fever, whooping cough and mumps, although none had the tragic results of the measles and strict isolation kept the worst effects at bay. The scale of rations, that deprived families of men on commando of meat, was immediately abandoned and, in the beginning inmates also received some vegetables. But the quality of the food deteriorated fairly rapidly. Although ovens were provided to bake bread, meat continued to be poor (although that sold in Johannesburg itself was unfit for human consumption). When tinned meat was introduced, the camp inmates complained that it gave them stomach troubles. The onslaught of disease, the strange, stuffy accommodation and the awful food may explain why Hobhouse and others pointed to Johannesburg camp as particularly bad.(https://www2.lib.uct.ac.za/mss/bccd/Histories/Johannesburg/)

Merebank camp could be described as a test case, an attempt to create a camp which avoided the mistakes of the past. It was established about September 1901, mainly to reduce the numbers in the Transvaal camps and to bring down the terrible mortality which was sweeping through the camp system. In some respects it could be considered a success for deaths were considerably lower. But its history is fraught with contradictions. For instance, with about 9,000 inmates, it was the largest camp in the entire system, although it was divided into three parts, Windermere, Hazelmere and Grasmere, each section housing about 3,000 people. This device made it possible to argue that the camp was within the recommended size. (https://www2.lib.uct.ac.za/mss/bccd/Histories/Merebank/)

A second inconsistency was its location. Merebank camp was based on the sub-tropical Natal coast, just south of Durban, in a climate which was very different from the crisp highveld air to which the Boers were accustomed. Humidity, strong winds and summer rains all contributed their discomfort, although cooler sea breezes helped to reduce the temperature in summer. Above all, it was built on low-lying, swampy ground, with sand blowing over everything and the floors and bedding constantly wet. Conditions were so poor that, after they had visited Merebank, the Ladies Committee recommended that the camp be moved. Despite this, Merebank remained where it was. The fact that it was on a railway line, close to Durban’s main water supply, on flat land, were all advantages which, in the eyes of the authorities, outweighed the potentially unhealthiness of the site. (https://www2.lib.uct.ac.za/mss/bccd/Histories/Merebank/)

Accommodation was a third anomaly. Initially the families were housed in the familiar bell tents and marquees but the climate made such accommodation even less suitable for women and children than it was in the Transvaal. As a result, wood and iron huts gradually replaced the tents. Built in rows of six rooms, they were not ideal, however, for they were hot, they lacked privacy and, by April 1902, they were leaking. In this subtropical climate fleas, lice and mosquitoes abounded, adding to the discomfort of the inhabitants. In some respects the staff were worse off. The teachers, for instance, as late as March 1902, were in dilapidated marquees and their food was cooked over an open fire outside. (

Education became a priority for the camps. Not only did schools keep the children occupied but they were also a means of inculcating the values of the British Empire into Britain’s future subjects. The Boers made some attempt to start their own schools, less vulnerable to imperial propaganda, but these were swiftly forbidden. Despite all the deficiencies, some children were able to prepare for national examinations. (https://www2.lib.uct.ac.za/mss/bccd/Histories/Merebank/)

Wisely, the superintendent, Hugh Moberley Bousfield did not try to restrict the Merebank people too much. Permission was regularly given for visits to the beach and picnics, swimming and fishing all relieved the monotony of camp life. The women were able to see their men off when they were transferred to prisoner-of-war camps overseas and visits to the Umbilo prisoner-of-war camp were occasionally allowed. Concerts, bazaars and sports days also occupied their time, as they did in other camps. If life in Merebank camp was hard, it was probably less tedious than it was in the up-country camps. (https://www2.lib.uct.ac.za/mss/bccd/Histories/Merebank/)

The first inmates arrived from Pretoria on 13 September 1901. It was often the trauma of the journey, in open cattle trucks, which the women remembered later, rather than life in the camp itself, both because of the discomfort and because of the fear of the unknown into which they were being sent. At least the food was better. Supply was much easier on the coast and fresh produce was readily available. Moreover, the Natal ration scale was always more generous than that of the ORC and Transvaal, and the Merebank inmates regularly received potatoes, onions and rice. Indian traders sold bananas and pineapples cheaply. But the meat was usually frozen and the children could not always get fresh milk. For some time there were no communal ovens and the women had to rely on open fires or the occasional primus stove. Eventually ovens were constructed in February 1902, making the cooking, which occupied so much of the day, more efficient. (https://www2.lib.uct.ac.za/mss/bccd/Histories/Merebank/)

No attempt was made to isolate the new arrivals with the result that measles came with them into the camp. Fortunately many of the camp inmates had already acquired an immunity to the disease so the results were less disastrous than they were in the up-country camps. Measles mortality reached its peak in October 1902 but it disappeared rapidly after that. Respiratory diseases, which might have included the aftermath of measles, lingered on for some months, along with diarrhoea and dysentery. Enteric, though never so fatal, was harder to eliminate completely. (https://www2.lib.uct.ac.za/mss/bccd/Histories/Merebank/)

Like many of their counterparts in other camps, the Boers received the news of the peace with mixed feelings. While they longed to return home, they found it difficult to accept that their leaders had laid down their arms. many responded with disappointment and confusion. The visits of General Schalk Burger early in June to explain why the Boers had made peace gave them only limited comfort. Repatriation was slow, partly because Merebank camp was used as an assembly point for returning prisoners of war. These men all had to be processed through the system, taking an oath of allegiance, before they could go home. The children were all issued with school leaving certificates and everyone was required to undergo a medical examination. The last group left on 10 December 1902 and the camp was finally closed in January 1903. (https://www2.lib.uct.ac.za/mss/bccd/Histories/Merebank/)

Personal Details

|

|

Name:

|

Mrs Jasper P C van der Westhuizen

|

Other

Names:

|

Westhuizen; Mrs Jasper

|

Born in

camp?

|

No

|

Age

died:

|

|

Died in

camp?

|

No

|

Gender:

|

female

|

Race:

|

White

|

Marital

status:

|

married

|

Nationality:

|

Transvaal

|

Occupation:

|

farmer

|

Registration

as head of family:

|

Yes

|

Unique

ID:

|

120766

|

Camp History

|

|

Name:

|

Jacobs

Siding RC

|

Name:

|

Heidelberg

RC

|

Age

arrival:

|

36

|

Date

arrival:

|

08/08/1901

|

Age

departure:

|

36

|

Date

departure:

|

22/10/1901

|

Reason

departure:

|

transferred camp

|

Destination:

|

Merebank RC

|

Tent

number:

|

647

|

Name:

|

Merebank

RC

|

Name:

|

Johannesburg

RC

|

Age

arrival:

|

36

|

Date

arrival:

|

08/07/1901

|

Date

departure:

|

06/08/1901

|

Reason

departure:

|

transferred

|

Destination:

|

Heidelberg RC

|

Tent

number:

|

RT 1716

No 3 Bldgs

|

Farm History

|

|

Name:

|

Modderbult

/ Moorderbult

|

District:

|

Heidelberg

|

Relationships

|

|

Mrs Jasper P C van der Westhuizen (Westhuizen;

Mrs Jasper)

|

|

is the mother of Master

Jacob van der Westhuizen (Jacobus )

|

|

is the mother of Master

Jan van der Westhuizen

|

|

is the mother of Master

Johannes van der Westhuizen (Johanna )

|

|

is the mother of Miss

Maria van der Westhuizen

|

|

is the mother of Miss

Martha Sophia van der Westhuizen (Martha)

|

|

is the mother of Miss

Petronella van der Westhuizen

|

|

is the mother of Master

Sarel van der Westhuizen

|

|

is the mother of Master

Jasper van der Westhuizen

|

|

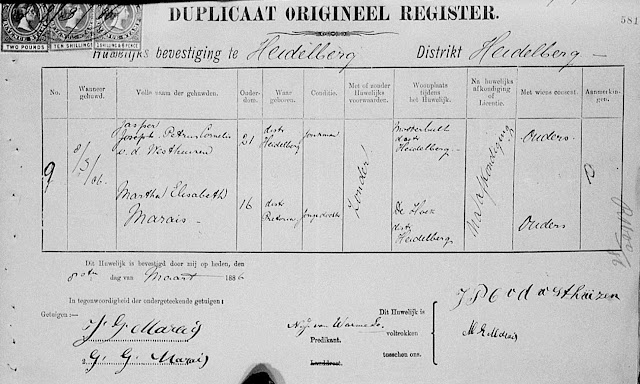

Sources

|

|

Title:

|

DBC 59

Heidelberg CR

|

Location:

|

Transvaal

|

Notes:

|

p.W 07

|

Title:

|

DBC 60

Heidelberg CR

|

Location:

|

Transvaal

|

Notes:

|

p.070

|

Title:

|

DBC 71

Johannesburg CR

|

Type:

|

Camp register

|

Location:

|

National Archives, Pretoria

|

Reference

No.:

|

71

|

Notes:

|

p.133

|